Last week took me to Inuvik to attend the Petroleum Show as part of my job as the policy advisor to the Senator for the Northwest Territories. While there, wearing my other hat as Aurora Award winning writer, I taught a workshop to a small but appreciative group and visited two classes at the new Inuvik High school – a grade 11 English class and a grade 7 one. I hadn’t been in a school for a number of years so I wasn’t sure how I might be received by students but they were polite and attentive and asked some nice questions.

Inuvik is a long way from anywhere but it’s an interesting place. Back in the 1950s the Federal government wanted to move people from the town of Aklavik (where the Mad Trapper met his end and was buried) because it was prone to flooding. They created Inuvik (then called by the imaginative names of East Three and later New Aklavik) with brand new hospitals, schools and other facilities. Aklavik is still there (the community motto is ‘Never Say Die’) but Inuvik is now the largest community in the region with 3500 people of mixed Inuvialuit, Gwi’chin and non-Aboriginal residents. With the completion of the Dempster Highway in 1979, it is also the most northerly town in Canada to which you can drive (though an extension of the highway to Tuktoyaktuk is currently under construction). One nice feature of visiting Inuvik in June is that the sun never goes down so it seems like mid- to late-afternoon 24 hours around. The Petroleum Show has been going on for a number of years as hopes rise and fall for the building of a pipeline to carry large stranded supplies of natural gas south. The show has plenty of interesting speakers from industry and government and this year featured Chief Clarence Louie from Osoyoos First Nation in BC and CBC radio and TV personality Rex Murphy. Not surprisingly the presentations are pretty pro-oil almost to the point of satire but they contain lots of useful information, too. And we had two nights of entertainment provided by local drummers, dancers and singers as well as imports The Good Lovelies and Shaun Majumder of This Hour has 22 Minutes.

But back to my school presentations.

One of the things I wanted to do was to talk to the kids about why we write and to encourage them to find their own voice in their writing. Inuvik has a rich cultural history that includes both Inuit and First Nations settlements, European whalers, oilmen and other outlaws, residential schools, Arctic explorers, the most northerly mosque in the world, a catholic church shaped like an Igloo, endless summer days and interminable winter nights (six weeks of each at the opposite ends of the calendar).

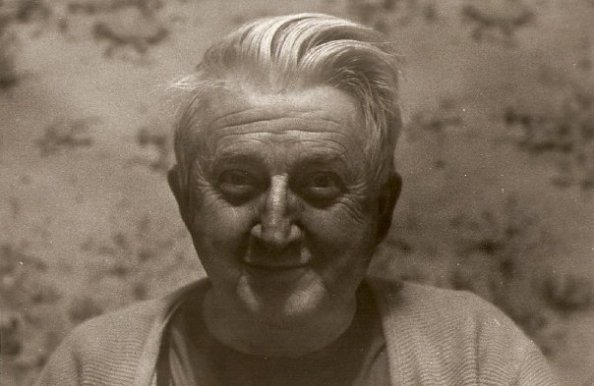

I talked about a lot of things but what seemed to capture their attention and imagination most was when I talked about my father and his father.

My grandfather was a pretty tough guy, particularly when it came to his kids. At one point in his life he was prosperous with a farm and two houses in town. Then his wife became an invalid (having given birth to 8 children by then) and with the cost of medical care combined the Maritime depression that started in 1920 (ten years before the rest of North America), he was soon reduced to a pretty hard scrabble existence. Discipline became the order of the day, with kids working on the farm or hired out to neighbours while Dad collected the wages. Disobedience wasn’t tolerated. The boys were physically punished, even, on occasion, horsewhipped. Two of his sons were huge men but their diminutive father had them cowed. Only my father, at 5’4” only an inch taller than my grandfather, stood up to the old man. Which was what led him to leave home at age 14, first to work on a farm in Annapolis Valley and later out to Saskatchewan on the last Harvest Excursion.

The five girls that made up the grade 11 class (3 students were away) listened to these stories with some interest but when I told what happened to my aunt they really perked up. Even the girl who kept her head on the desk, feigning exhaustion (or indifference), sat up and took notice. When my aunt was about 16, she was very pretty with a gorgeous head of hair. One day she defied her father. His response was to shave her head with the sheep shears.

It’s surprising that my father – who clearly inherited his own dad’s stubborn streak – turned out almost the opposite of him. He was a gentle man, much more likely to laugh or make a joke when things were tough than to get mad. Our discipline was seldom physical (though the few spankings were well deserved) but usually involved exile to our room, temporary loss of privileges and the ever dreaded calm explanation of what we had done wrong and why he was so disappointed in us. Good behavior on the other hand was rewarded by greater personal freedom and kind words for praise. Maybe it’s no surprise that my father’s death when I was 24 is still the saddest day of my life.

As I said, my dad went west in 1928 when he was eighteen. He worked on a Saskatchewan farm for two years before the Depression cost him his job. He went down to Montana (an illegal alien) to work on a sheep ranch his older brother was running but they soon parted ways. For the next six years, my dad rode the rails as a hobo, travelling to all 48 states and every province in Canada (Newfoundland was the sole exception – but it wasn’t a province then). He worked on Hoover (Boulder) Dam in Nevada, picked grapes in California, worked in the kitchen of a New York hotel where Red Skelton was the headliner and as an orderly in a Boston mental hospital. It was a point of pride for him that he was never broke and never out of work for more than a week. He returned home to Nova Scotia briefly in 1936 when his brother accidentally killed his sister – with the proverbial ‘unloaded’ gun. After a few months he heard of work at a mine in Noranda, Quebec and spent the rest of the 30s working there before joining the Royal Canadian Engineers at the outbreak of World War II. Years as a hobo had given him an independent streak and a dislike for men in uniform giving him orders; he made Sergeant three times (you figure it out). As the oldest man in his unit (at 32) he earned the nickname ‘Pops’ and was a popular choice as chaperon when the boys wanted to go on a (double) date. That’s how he met my mother, an English rose, 14 years his junior. And the rest is history.

So how do I know all this? Because instead of reading to us at bedtime, he would sit at the head of our bunk bed (me on the bottom and Bill on top) and tell us endless stories – of growing up, working and travelling in the 30s, the War – to the point that we began to have favorites and would request them some nights. Most often he would oblige but sometimes he would have a new story for us – more complex and mature as we aged. It was how I learned our family history. It’s how I got my moral compass. It’s how I became a man. And a writer. I hope by sharing some of those stories with those kids in Inuvik they will look at their own parents and their own lives in a different light. Everyone does have a story to tell and I hope they find theirs.

My father lives on in me and my brothers – in memory yet green.

Happy Father’s Day.